This series, Linux for Hackers, was developed to help familiarize the uninitiated into the world of using Linux for hacking. If you have not read Part 1-6, you can find them here.

Any self-respecting hacker must be able to script. For that matter, any self-respecting Linux administrator must be able to script. With the arrival of the Windows PowerShell, Windows administrators are increasingly required to script as well to perform automated tasks and be more efficient.

As a hacker, we often need to automate the use of multiple commands, sometimes from multiple tools. To become an elite hacker, you not only need to have advanced shell scripting skills, but also the ability to script in one of the widely-used scripting languages such as Ruby (Metasploit exploits are written in Ruby), Python (many hacking tools are Python scripts), or Perl (Perl is the best text manipulation scripting language).

We will start with basic shell scripting, move to advanced shell scripting, and then to each of these scripting languages developing hacking tools as we go. Our ultimate goal will be to develop enough scripting skills to be able to develop our own exploits.

In a previous post, I showed you how to put together a simple script using nmap to scan a range of IP addresses to check for a particular port availability. We will need that script here, as we will be adding new functionality to it after completing some preliminaries.

Step 1: Types of Shells

A shell is an interface between the user and the operating system. This enables us to run commands, utilities, programs, manipulate files, etc.

There are a number of different shells available for Linux. These include the Korn shell, the Z shell, the C shell, and the Bourne again shell (or BASH).

As the BASH shell is available on nearly all Linux and UNIX distributions (including Mac OS X, and Kali), we will be using the BASH shell here, exclusively.

Step 2: BASH Basics

To create a shell script, we need to start with a text editor. You can use any of the text editors in Linux including vi, vim, emacs, gedit, kate, etc., but I will be using Leafpad here in these tutorials. Using a different editor should not make any difference in your script or its functionality.

Step 3: Built in BASH commands

Besides being able to run any system commands, utilities or applications from a BASH shell script, the BASH shell includes some of its own commands. These include;

:, ., break, cd, continue, eval, exec, exit, export, getopts, hash, pwd, readonly, return, set, shift, test, [, times, trap, umask and unset,alias, bind,builtin, command, declare, echo, enable, help, let, local, logout, printf, read, shopt, type, typeset, ulimit and unalias.

I will address these commands in a later tutorial, but I want you to know that this shell has built in commands that have their functionality within the BASH shell.

Step 4: Comments

Like any coding, we may want to add comments. Comments are simply notes to ourselves or anyone else that reads the code as to what we were trying to do with the script or that section of the script. These notes or “comments” are not read or executed by the interpreter.

The BASH shell enables comments by preceding a line with the “#”, so if I wanted to note that this was my first script, I could write in my text editor;

This is my first script!

The interpreter would ignore everything after the # and then move to the next line.

Step 5: “Hello, Hackers-Arise!”

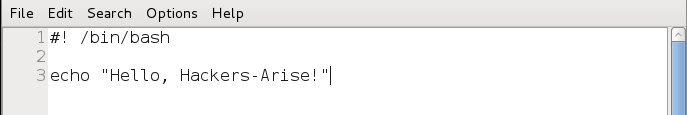

For our first script, we will start with a simple script that returns a message to the screen that says “Hello, Hackers-Arise!”.

We start by entering the shebang or “#!”. This tells the operating system that whatever follows the shebang is the interpreter we want to use for our script.

We then follow the shebang with /bin/bash indicating that we want the operating system to use the BASH shell interpreter. As we will see in later tutorials, we can use other interpreters such as PERL or Python, but here we want to use the BASH interpreter.

#! /bin/bash

Next, we enter echo, a command in Linux that tells the system to simply repeat or “echo” back to our monitor (stdout) what follows. In this case, we want the system to echo back to us “Hello Hackers-Arise!”. Note that the text or message we want to “echo back” is in double quotation marks.

echo “Hackers-Arise!”

Now, let’s save this file as HelloHackersArise and exit from our text editor.

Step 6: Set Execute Permissions

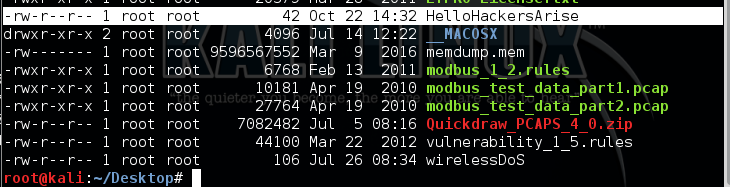

When we create a file, it’s not necessarily executable, not even by us, the owner. Let’s look at the permissions on our new file, by typing ls -l in our directory.

As you can see, our new file has rw-r–r– (644) permissions. The owner of this file only has read (r) and write (w) permissions, but no execute (x) permissions. The group and all have only read permission. We need to modify it to give us execute permissions in order to run this script. We do this with the chmod command. To give the owner, the group, and all execute permissions, we type:

kali > chmod 755 HelloHackersArise

Now when we do a long listing (ls -l) on the file, we can see that we have execute permissions.

kali > ls -l

Step 7: Run HelloHackersArise

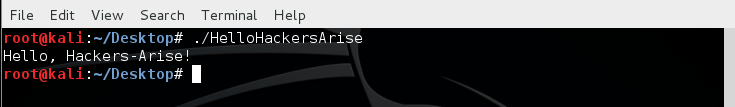

To run our simple script, we simply type:

kali > ./HelloHackersArise

The ./ before the file name tells the system that we want to execute this script in the current directory. This means don’t look in the directories in the PATH variable for this file, but rather look just in my current directory and run HelloHackersArise

When we then hit enter, our very simple script returns to our monitor.

Hello Hackers Arise!

Success! We just completed our first simple script!

Step 8: Using Variables

So, now we have a simple script. All it does is echo back a message. If we want to create more advanced scripts we will likely want to add some variables.

Variables are simply an area of storage where we can hold something in memory. That “something” might be some letters or words (strings) or numbers. It can help to add functionality to a script that has values that might change.

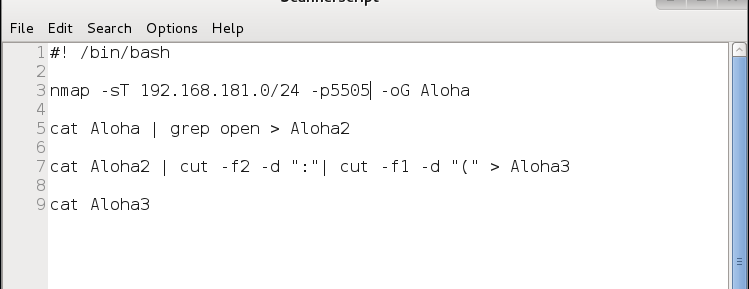

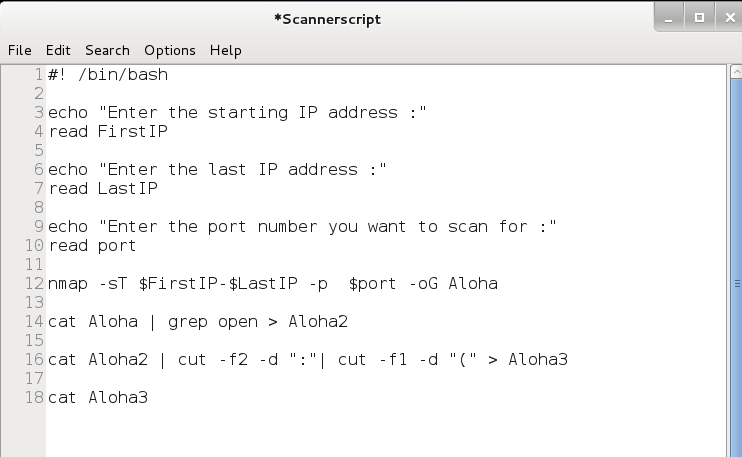

Let’s go back to the script we wrote earlier to use nmap to scan for vulnerable machines with a particular port open. Remember, the (in)famous hacker, Max Butler, used a similar script to find systems with the Aloha POS that he was able to hack for millions of credit card numbers.

As you can see, this script was written to scan a range of IP addresses looking for port 5505 open (the port Aloha left open for tech support), and then create a report with all the IP addresses with this port open. The IP address range is “hard coded” into the script and can only be changed by opening and editing the script file.

What if we wanted to alter this script so that it would prompt us or any user for the range IP addresses to scan and the port to look for? Wouldn’t it be much easier to use if we were simply prompted for these values and they were then entered into the script?

Let’s take a look at how we could do that.

Step 9: Adding Prompts & Variables to Our Script

First, we could replace the specified sub-net with a IP range. We can do this with a variable called “FirstIP” and then a second variable named “LastIP” (the name of the variable is irrelevant, but best practice is to use a variable name that helps you remember what it holds).

Next, we can replace the port number with a variable named “port“. These variables will simply be storage areas to hold the info that the user will input before running the scan.

Next, we need to prompt the user for these values. We can do this by using the echo command we learned above in writing the HelloHackersArise script.

So, we can simply echo the words “Enter the starting IP address :” and this will appear on the screen asking the user for the first IP address in their nmap scan.

echo “Enter the starting IP address :”

Now, the user seeing this prompt on the screen, will enter the first IP address. We need a way then to capture that input from the user. We can do this by following the echo line with the read command followed by the name of the variable. The read command takes a value entered at the keyboard (stdin) and puts it into a variable that follows it.

read FirstIP

The above command will put the IP address entered by the user into the variable, FirstIP. Then we can use that value in FirstIP throughout our script.

Of course, we can do the same for each of the variables by first prompting the user to enter the information and then using a read command to capture it.

Next, we just need to edit the nmap command in our script to use the variables we just created and filled. When we want the value stored in the variable, we can simply preface the variable name with the $, such as $port.

So, to use nmap to scan a range of IP addresses starting with the first user input IP through the second user input IP and look for a port input by the user, we can re-write the nmap command like this:

nmap -sT $FirstIP-$LastIP -p $port -oG Aloha

Now, as the script is written, it will scan an IP address range starting with FirstIP and ending with LastIP looking for the port the user input. Let’s now save our script file and name it Scannerscript.

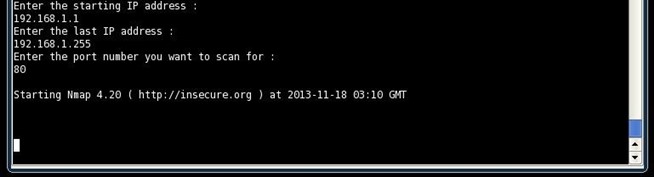

Step 10: Run It with User Input Variables

Now we can run our simple scanner script with the variables that tell the script what IP address range and port to scan without having to edit the script.

kali > ./Scannerscript

As you can see, the script prompts us for the first IP address, then the last IP address and the port we want to scan for. After collecting this info, it then does the nmap scan and produces a report of all the IP addresses in the range that have the port open that we specified.

Stay Tuned for More Linux for Hackers

Make certain to save this script as we will return to it in future tutorials and add even more functionality to it as we learn more about Linux and shell scripting for hackers.

For more on using Linux for hacking, check out my book “Linux Basics for Hackers” now available here on Amazon.