Welcome back, my hacker apprentices

Recently, I started my password cracking series with an introduction to the principles and technologies involved in the art of cracking passwords. In past guides, I showed some specific tools and techniques for cracking Windows, online, Wi-Fi, Linux, and even SNMP passwords. This series is intended to help you hone your skills in each of these areas and expand into some, as yet, untouched areas.

Very often, hackers new to password cracking are looking for a single tool or technique to crack passwords, but unfortunately, that does not exist. That’s fortunate for network security, though. Each type of password requires a unique strategy tailored to the situation. The situation can be the type of encryption (MD5, SHA1, NTLM, etc.), remote vs. offline, salted or unsalted, and so on. Your password-cracking strategy must be specific to the situation.

In this tutorial, I want to discuss the password-cracking strategy. Many newbie password crackers simply run their password-cracking tool and expect a breakthrough. They run huge wordlists and hope for the best. If it doesn’t crack the password, they are lost. Here I want to develop a multi-iteration strategy for password cracking that will work on the vast majority of passwords, though not all. No strategy will work on all passwords except the CPU and time-intensive brute force cracking.

Developing a Password-Cracking Strategy

I’m assuming here that we are after more than a single password. Generally, password cracking is an exercise of first capturing the hashes. In Windows systems, these are in the SAM file on local systems, LDAP in active directory systems, and /etc/shadow on Linux and UNIX systems. These hashes are one-way encryption that is unique for every password input (well, nearly every password input, to be precisely accurate). In each case, we need to know what encryption scheme is being used to crack the hash.

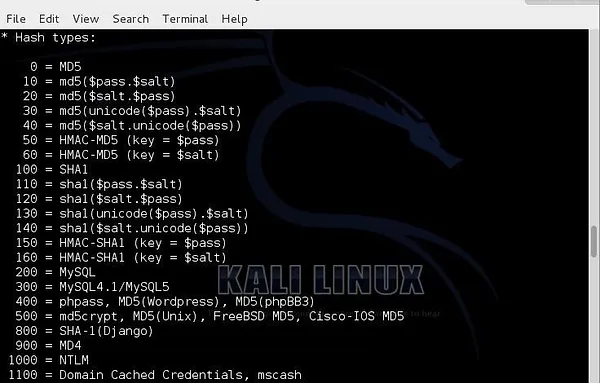

For instance, Linux and Unix systems use MD5 and modern Windows systems use HMAC-MD5. Other systems may use SHA1, MD4, NTLM, etc. Make certain you know what hash is being used on the system you are trying to crack, otherwise you will spend hours or days without satisfactory results.

All that having been said, John the Ripper has an automatic hash detector that is correct about 90% of the time, but when it is wrong, there is no way to know. In Cain and Abel as well as hashcat, we must tell the tool what type of hash we are trying to crack.

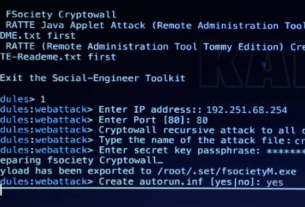

Here we can see a screenshot of the types of hashes that we can crack using hashcat and their numeric values.

Brute Force Short Passwords

Although it might seem contrary to common sense, I often start by trying to brute force very short passwords. Although the brute force of long passwords can be very time-consuming (days or weeks), very short passwords can be brute-forced in a matter of minutes.

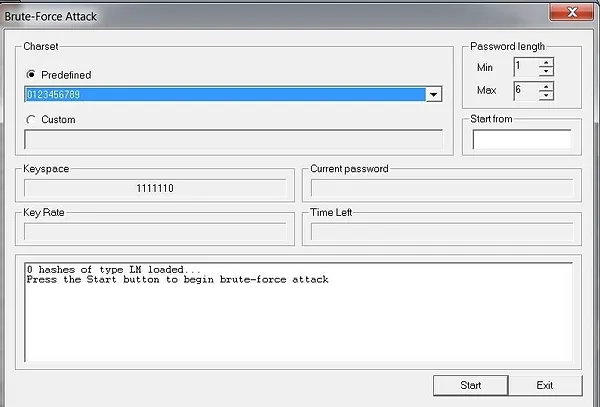

I start by trying to brute force passwords of six characters or less. Depending on my hardware, this can usually be accomplished in a matter of minutes or hours. In many environments, this will yield at least a few passwords.

In addition, I will also try to brute-force all numeric passwords at this stage. Number passwords are the easiest to crack. An 8-character numeric password only requires that we try 100 million possibilities, and even a 12-character number password only requires 1 trillion possibilities. With powerful hardware, we can do this without barely breaking a sweat.

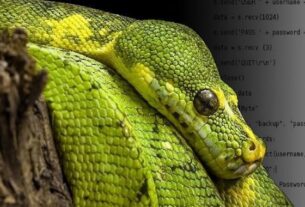

Here we have configured Cain and Abel to brute force 6-character passwords that are only numbers.

Low-Hanging Fruit

Once we break a few short passwords by brute force, we will still likely have a file that has many, many hashes in it. If we trying to compromise an institutional or corporate network, we usually only need to crack a single password to begin the network compromise.

Although the user whose password is cracked may have limited rights and privileges, there are many ways to escalate privileges to sysadmin or root. This means that if we can crack a single password on a network, we can likely take down the entire network.

All of the above having been said, let’s next go after any low-hanging fruit. That means let’s go next after those passwords that are easiest to crack. For instance, if we know the institution has a password policy that all passwords must be 8 characters, many people will make their passwords the absolute minimum.

To attempt a quick and dirty pass on these hashes, simply choose a list of dictionary words that are eight characters. Running through the millions of words in such a list will generally only take a few hours and is likely to yield a significant portion of the passwords.

Try Common Passwords

Human beings, although we think we are unique, tend to think and act similarly. Just like pack animals, we follow the herd and act similarly. The same can be said for passwords.

Users want a password that fulfills their organization’s minimum password policy but also is easy to remember. That’s why you will see passwords, such as “P@ssw0rD” so often. Despite its obvious simplicity, it fulfills a password policy of a minimum of 8 characters, uppercase and lowercase letters, a special character, and a number. Believe it or not, this password and its variations are used numerous times.

Knowing that humans tend to use these types of passwords, in my next iteration on the password hash list, I will try a password list of commonly found passwords. Numerous sites on the web include wordlists of cracked or captured passwords. In addition, you might try scraping the web to capture as many passwords as possible.

Combine Words with Numbers

Running through the low-hanging fruit in Step #2 and common passwords in Step #3 will likely yield at least a few passwords and the time it consumes is minimal. Now we want to attack the remaining hashes and take the next step in complexity.

In this iteration, we will run the remaining hashes through a wordlist that has longer dictionary words and dictionary words with numbers. Users, because they are forced to change passwords periodically, will often just add numbers to the beginning or end of their passwords. Some of our password cracking tools like Hashcat and John the Ripper allow us to use rules to apply to wordlists to combine words, append and prepend numbers, change cases, etc.

Hybrid Attack

By now we have usually cracked over 50% of the passwords in Steps #1 through #4, but we have the harder work ahead to crack the more intransigent passwords. These passwords will often include special characters and combined words.

These would include such passwords as “socc3rmom” and “n3xtb1gth1ng”. These are relatively strong passwords including special characters and numbers, but because they include variations on dictionary words they are often easily crackable.

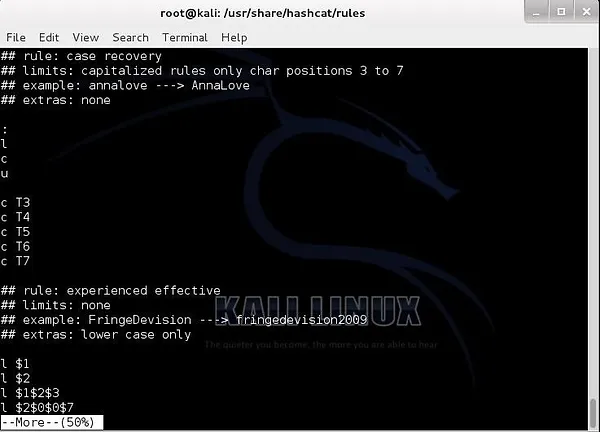

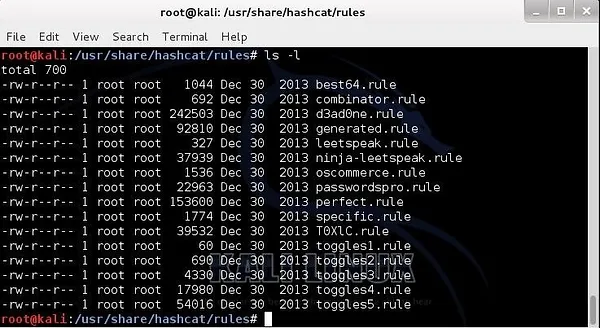

Next, we need a password list that combines dictionary words with numbers and special characters. Fortunately, this is something that John the Ripper does automatically, but other password crackers (Cain and Abel) don’t necessarily. Hashcat can be run with one of its many rules sets to combine words and special characters to your wordlist.

In this screenshot, we can see the combinator rule in Hashcat that adds upper-case characters to combined words

Finally, if All Else Fails…

If all else fails, you are left to brute force the passwords. This can be very slow with a single CPU, but can speeded up 1000x or more with a botnet, a password-cracking ASIC, or a very fast multiple GPU password cracker (I’ll be doing tutorials on each of these shortly). Among the fastest of these, a 25 GPU password cracker is capable of 348 billion hashes per second!

Even when we are left with a brute force attack, we can be strategic about it. For instance, if we know that the password policy is a minimum of 8 characters, try brute forcing with just eight characters. It will save you time and likely yield some passwords.

In addition, you can choose your character set. Once again, if we know that the password policy is uppercase, lowercase, and a number, choose only those character sets to brute force.

Finally, some password crackers like hashcat (look for my upcoming tutorial on hashcat) have built-in “policies” that you can choose to attempt brute force. These are similar to strategies and help by shaping your attacks based on the password-construction protocol followed by a company or group.

These rules can be used in other password-cracking tools such as John the Ripper. Here we can see a listing of these rules in Hashcat (these can be used in John the Ripper, as well).

It is important to be successful at password cracking that you follow a systematic strategy, no matter what tool you are using, that requires multiple iterations to crack the most passwords. This strategy generally works from the passwords that are easiest to crack to the most difficult.

Of course, this strategy will in part be dependent upon the tools you are using, the wordlists that you use, and the password policy of the victim. Although I have laid out here my password-cracking strategy, yours may be different and need to be adapted to the environment you are working in.